Challenges and Need for Developing Green Wavelength Technology in Life Science Fluorescence Applications

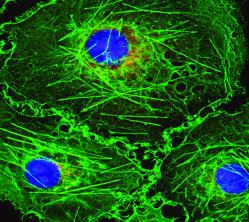

In microscopy and analytical instrumentation, a researcher or clinician may need to excite several fluorophores in a sample in order to generate a useful fluorescence map of the cell or tissue of interest. This typically would include a nuclear marker such as DAPI, a green-emitting fluorophore such as FITC or GFP, and a red-emitting fluorophore such as mCherry, TRITC, or Texas Red. These red-emitting dyes can be efficiently excited using an arc lamp with a strong peak in the 550 nm region and another at 580 nm.

Today’s microscopists increasingly favor the use of light-emitting diodes (LEDs) for life science fluorescence studies. Benefits of LED technology include a long lifetime, increased stability, and elimination of consumables, toxic waste, and the costs associated with mercury disposal. LED technology is used not only in fluorescence microscopy systems to image the cells or tissues under investigation, but also in several other fluorescence-based technologies such as fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS) and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) instruments used for diagnostic purposes. Many clinical applications requiring a high-power light source to cover various wavelength ranges are converting to LED systems that can now meet requirements previously achievable only with mercury, metal halide, or xenon lamp technology.

When technology in microscope light sources originally moved to LEDs in the early 2000s, fluorescence work in the green gap (540 to 590 nm) excitation range was a challenge with no solution. Our article in the July 2020 issue of Microscopy Today explains how technology has adapted to provide LEDs that match the excitation of fluorophores typically used in multiplex fluorescence imaging. Read the article online by clicking here.